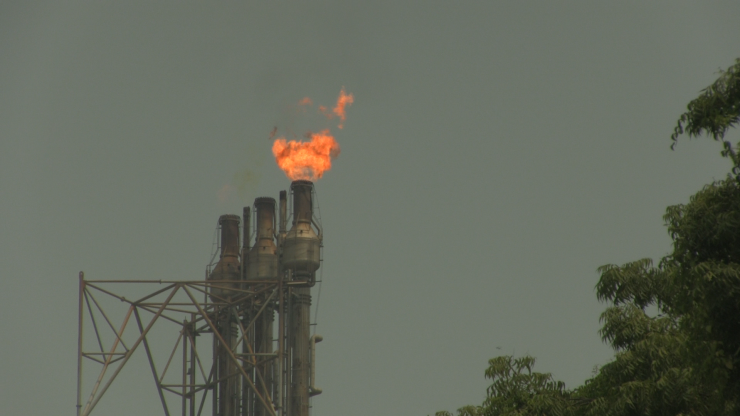

In August 9, 2018, at 2.45pm, an explosion shattered the windows of the SRA (Slum Rehabilitation Authority) residential buildings in Mahul. The explosion occurred in a part of the BPCL (Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited) refinery, which is only one of the many refineries that are as close as 50m from the residential complexes of the SRA. The film would like to use this event as a point of insertion to explore the grossly hazardous living conditions of the residents who have been “resettled” and “rehabilitated” from various parts of Mumbai due to the pipeline projects. The injustice committed against the residents of the SRA colonies does not end at being displaced very far away from their source of livelihood, education, and health support systems, but is exacerbated by the fact that they have been moved to an area which would otherwise be inhabitable.

The precarity of the residents operate on multiple levels, a lot of which stem from the proximity of the buildings to these refineries. The health issues faced by the residents are many; including but not limited to stomach and skin infections, respiratory issues, low immunity and even cancer. From our conversations, another issue that was raised was the resurfacing of dormant health concerns that people have faced within a few months of moving to Mahul, triggered by the inhospitable environment. Moreover, the recent fire is just a prelude to what are the many threats that residents continue to face.

Even though National Green Tribunal (NGT) declared the area inhabitable in 2015, and also asked the Maharashtra Pollution Control Board (MPCB) to define a buffer zone between the industrial and residential areas, this has still not been defined. The residents want to be moved from Mahul and want a permanent solution to the continued violations of their basic rights. As a part of the Ghar Bachao Ghar Banao Andolan, a rally was organised by the residents of Mahul and others affected by the various pipeline projects (which as the displaced communities argue, should have been underground enabling them to return to their homes) in June 2018 to demand better rehabilitation. The protest continues today. The film will attempt to explore the various complexities of rehabilitation and the rights of migrants in Mahul.

During our visits to the area, we were able to talk to people participating in the protest. We talked to Anita Dhole and BR Verma who have been constantly a part of the movement, and who we intend to make central figures within the narrative of the film. Issues of cleanliness and hygiene were also brought forward by the people who we talked to, and the site was evidence for the complacency of the authorities about the living conditions of the people, motivating the residents to believe that they have exiled to die.

Building no. 29 from where the refineries can be seen very clearly. The multiple refineries, one of which had a blast on August 9 2018. They are barely a 30-40 meters away from where the buildings start.

Hygiene conditions are quite poor. Residents even complained that sometimes there is a layer of oil in the water that they get:

The first few buildings that were made were reserved for the police forces in the area. However, the buildings remain empty because they refused to live in an area which is so inhabitable. But BMC has no qualms about shifting more and more people from demolished settlements across Mumbai to these buildings.

References:

https://countercurrents.org/2018/06/29/mumbais-urban-poor-hit-streets-today-after-governments-failure-to-rehabilitate-them/

https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/mumbai/tribunal-orders-probe-into-pollution-in-mahul/

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/feb/26/mumbai-poor-mahul-gentrification-polluted

https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/mumbai/mpcb-issues-closure-notice-to-two-mahul-companies/article24147226.ece

https://www.mid-day.com/articles/mumbai-60-percent-of-mahul-residents-have-skin-disease-or-asthma-trouble/19572163

http://www.freepressjournal.in/mumbai/mumbai-mahul-gaon-residents-raise-issues-of-cleanliness/1074664